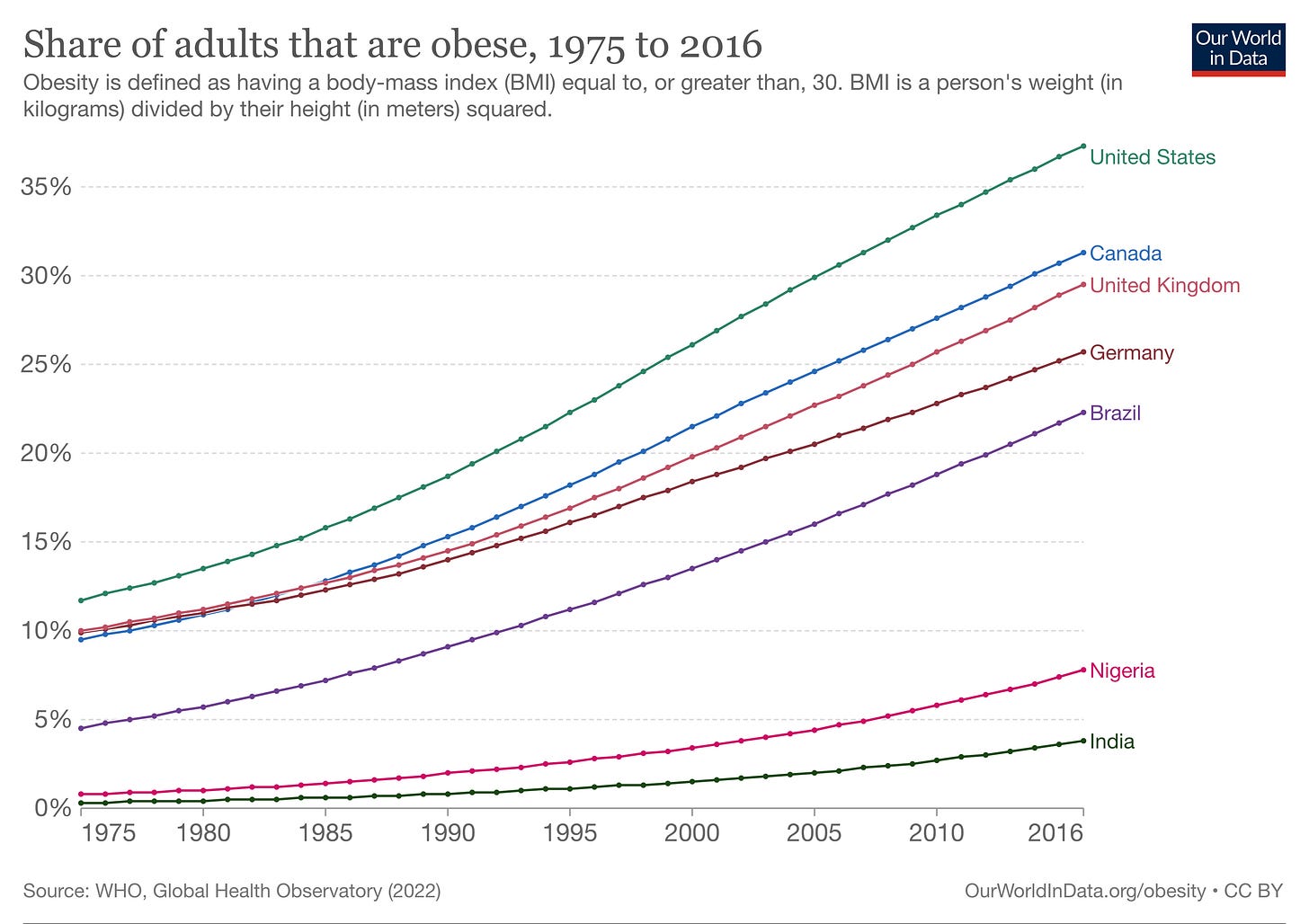

Is obesity a disease or a lifestyle choice? It behooves us all to understand obesity, because it’s incredibly common and impactful. The odds are good that you, or someone you care about, is affected by obesity. Globally, roughly 1 in 7 adults fit the official (and highly imperfect) definition of obesity: a BMI greater than or equal 30. In America, that number has surpassed 1 in 3, and Canada is not far behind. Many more adults and children are considered overweight, and on a trajectory towards obesity.

Obesity is a global challenge, and is one of the leading causes of preventable death worldwide. Obesity increases the risk of developing a wide range of serious medical issues, including hypertension, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea, some cancers (e.g. breast and colon), as well as mental health challenges. The massive toll of obesity in causing premature deaths is shown below for North America using data from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study.

Over the past few years, I’ve been educating myself about obesity through scientific, medical, and advocacy organizations, as well as my stellar podcast guests (see links below). Today, I want to shed some light on the science of obesity, and how my thinking has evolved.

One the surface, obesity appears to be a lifestyle choice. Proponents of this view point out that there was no global obesity crisis until we started eating a lot more and moving a lot less. It follows that the solution should be simple: eat less and move more! People may also hold this view because of personal experience: “I’m able to control my weight through diet and exercise, so others should too.”. I’m ashamed to admit that I held this naive view myself, until I began to dig more deeply into the science.

This view of obesity certainly has some elements of truth to it. The obesity epidemic can be largely attributed to changes in diet, lifestyle, and food environment - our genes haven’t changed. It’s also true that our body fat stores are shaped by our energy balance: “calories in versus calories out”. In theory, we can control this balance through diet and exercise. It’s well documented that people generally lose body fat when they slash their daily calorie intake or if they increase physical activity (without increasing food intake). We see this play out on TV in The Biggest Loser, and in the scientific literature, across countless weight loss studies (though weight-loss maintenance is a different beast).

So, what’s wrong with the “lifestyle choice” view? First of all, it’s woefully incomplete. It fails to recognize the bigger picture - that body weight is determined by a wide range of genetic, environmental, and social factors, many of which are not in our control. Second, this view is fertile ground for harmful and unfair judgements of people with obesity as lazy, lacking in willpower, uneducated, etc. Weight biases and stigmas are incredibly common, though we may not recognize them in ourselves (check out Harvard’s suite of tests for implicit biases!).

Decades of science have revealed that body weight is a biologically regulated process - analogous to the way that body temperature is regulated. Our bodies are more tolerant of weight gain than weight loss, which we unconsciously resist using both sides of the energy balance equation. The way this plays out for each of us depends on our genes, our environment, our physiology, and the interaction between these drivers.

Our desire for food is heavily influenced by a complex network of hormones and other signals, in which the brain and gut have a central roles. While it’s natural to believe that hunger is a perfect cue, our bodies are not always steering us to an “ideal” body weight. After weight loss, our appetite, hunger, and satiety cues drive us to regain the weight. Not surprisingly, many obesity medications work by regulating appetite and food reward - they do this in part by altering brain and gut signals, like GLP-1 receptor agonists (semaglutide/ Ozempic/ Wegovy).

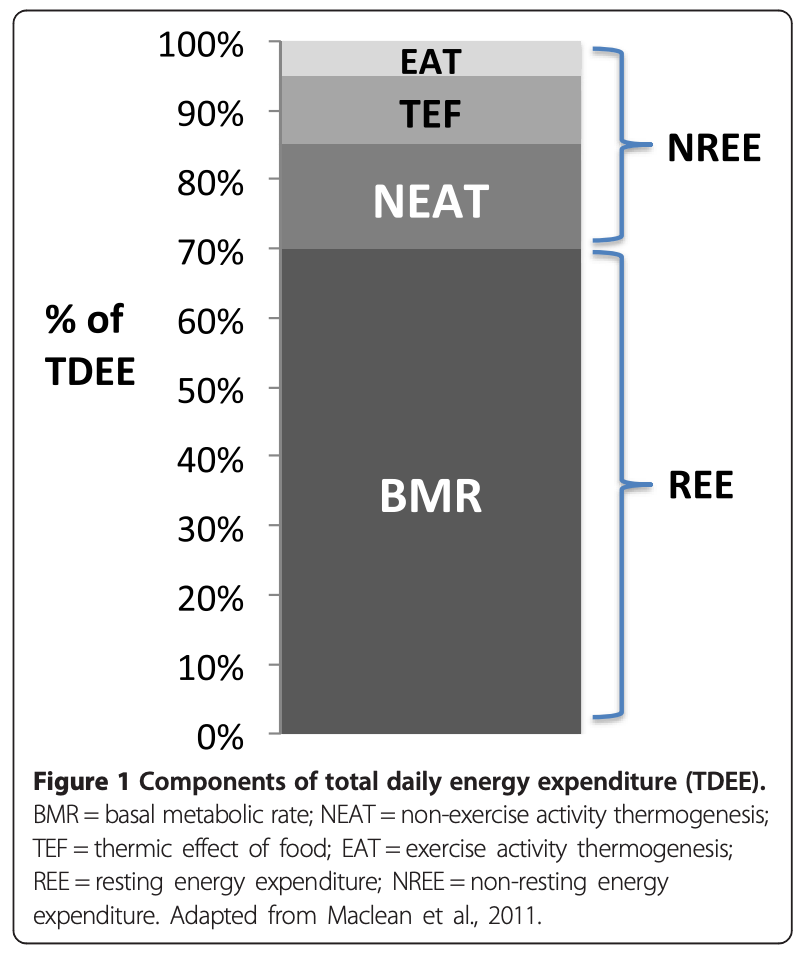

On the other side of the equation, the calories that we burn by adding a few modest workouts to our week are only the tip of the iceberg. The vast majority of energy that we spend is unconscious - it’s spent keeping us alive, digesting our food, and on NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis). In fact, one way that our bodies resist weight loss is by decreasing our unconscious non-exercise activity. One study found evidence of metabolic alterations six years after the Biggest Loser competition.

Among obesity experts, “metabolic adaptation” is widely recognized as one of the key reasons that it’s hard to lose weight, and even harder to keep it off. This term describes changes in appetite, satiety, metabolism, and energy output that occur when we restrict calories; those changes drive our bodies towards a higher weight (fat mass). According to a 2015 study: “To maintain weight loss, individuals must adhere to behaviours that counteract physiological adaptations and other factors favouring weight regain. It is difficult to overcome physiology with behaviour.”

Obesity experts are also aligned on the fact one of the major drivers of obesity is the mismatch between our biology, which evolved when food is scarce, and today’s plentiful food environment. As described in this study: “the development of obesity and resistance to weight loss is due to an interaction between physiology and behaviour in a food, lifestyle and marketing environment that facilitates over-consumption of energy and low levels of physical activity energy expenditure.”

When you recognize the fact that body weight is biologically regulated, and that it’s impacted by genes, stress, sleep, our food environment (food security, food access, food advertising, etc), and social determinants of health, it’s hard to argue that obesity is a lifestyle choice. To be clear, these factors do not invalidate the role of “calories in calories out” on body weight; they exert themselves through energy balance. For example, inadequate sleep has been consistently shown to impact appetite, food preferences, and food intake, leading to weight gain. Likewise, ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are associated with weight gain, but this can be explained by the fact that people tend to consume more calories when consuming UPFs.

These scientific insights are shaping the way that experts think and talk about obesity. Many organizations now define obesity as a disease - including the World Health Organization, American Medical Association, Obesity Canada, and more. Obesity is defined by the Obesity Medicine Association as a “chronic, relapsing, multi-factorial, neurobehavioral disease, wherein an increase in body fat promotes adipose tissue dysfunction and abnormal fat mass physical forces, resulting in adverse metabolic, biomechanical, and psychosocial health consequences.” The decision to declare obesity as a disease typically considers both the medical argument and the societal implications of this label. For example, the Obesity Society Council stated in 2008:

“We believe that considering obesity a disease will: (1) benefit our citizenry by soliciting more resources for prevention and treatment of, and research on, obesity; (2) encourage health-care professionals to view treating obesity as a vocation worthy of effort and respect; and (3) reduce the stigma and discrimination experienced by many persons with obesity.”

To me, one of the strongest arguments for defining obesity as a disease is the fact that weight loss can eliminate a large number of weight-related health issues, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, joint conditions, and more. That said, body weight is a highly flawed predictor of health, and some people’s bodies have a higher tolerance for greater fat stores than others (see this 2023 study).

The global shift towards defining obesity as a disease is not without controversy. Some people feel that this label further stigmatizes larger bodies and implies that it’s not possible to be healthy in a larger body. Others worry that it shifts the focus away from personal responsibility, the power of lifestyle changes, and food policy issues. While these concerns are legitimate, I don’t think they invalidate the notion that obesity is a chronic disease. Even if obesity is designated as a disease, it does not mean that people with obesity are somehow inferior - less beautiful, strong, talented, and so on. Likewise, recognizing obesity as a disease doesn’t mean that lifestyle choices don’t matter - they’re just not the whole story. Ditto for the critical role of our food environment, food advertising and food policies.

Back to our original question: is obesity a disease or a lifestyle choice? My current view echos that of leaders in the field: obesity is a disease for which lifestyle choices can make a difference, but for which there are many factors beyond our control. There is no quick fix for obesity. To reverse the obesity epidemic, we will need to pull many levers, across individuals, governments, and societies. I cringe thinking of my naive “just less eat and move more” view, the judgements I’ve passed, and my ignorance about the roles of each person’s physiology and context.

My opinion on this topic has been highly influenced by Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, a leading obesity medicine physician, whom I had the pleasure of interviewing for my podcast. She has treated countless people with obesity of all ages, and is a vocal advocate for addressing weight stigmas and health inequities. It’s her strong conviction that every person with obesity should have access to the whole toolkit - including medications and surgery. I encourage you to check out our conversations below, as well as the other resources provided.

Thanks for reading and sharing this article. I will be taking a writing hiatus this summer, so you won’t be hearing much from me for a while. ‘Till next time, be well.

Best,

Related Podcast Episodes

Weight Loss Medications to Treat Obesity with Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford. Get Real Health with Dr. Chana Davis (Ep 60) on my website, Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Weight Bias and Weight Stigma with Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford. Get Real Health with Dr. Chana Davis (Ep 28) on my website, Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Understanding & Treating Obesity with Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford. Get Real Health with Dr. Chana Davis (Ep 27) on my website, Apple Podcasts or Spotify.