Did you know that alcohol increases the risk of cancer, even with light to moderate drinking? A 2020 study estimated that over 700,000 cancer cases worldwide were attributable to alcohol, of which over 140,000 were driven by light to moderate drinking.

I find myself taking such health hazards more seriously as I shift from the invincible mindset of youth to the “I might not be healthy forever?!” middle-age awakening. I typically enjoy a few glasses of wine on weekends and have been wondering how much of a toll this takes. So, I explored the data and wanted to share my findings.

Let’s start with three key facts about alcohol and cancer.

Alcohol is a proven carcinogen. It’s strongly linked to at least seven types of cancer: mouth (oral cavity), throat (pharynx), oesophagus, voice box (larynx), colon, rectum, liver, and female breast.

All types of alcohol increase the risk of cancer (sadly, even wine). It’s the ethanol that matters. Alcohol increases cancer risk in these sites through DNA damage from acetaldehyde (a product of alcohol metabolism), oxidative stress, increased sensitivity to other harmful chemicals, and more.

The more you drink, the greater your cancer risk. The more ethanol we are exposed to, the more we damage our cells and promote cancer-causing alterations.

To make an informed choice about alcohol, we need to flesh out these risks in more detail.

How much does alcohol increase your cancer risk?

Heavy drinking dramatically increases the risk of several types of cancer. We’re talking five-fold higher risks of some mouth and throat cancers and more than double the risk for liver and gallbladder cancer, not to mention many other health risks.

The toll of drinking alcohol is harder to pinpoint for light to moderate drinking. If a group of people shift from teetotaling to just one drink a day, we’d expect roughly two more women out of 100 to develop cancer and one more man out of 100 over their lifetimes, according to a large Australian study.

Light drinking has a more significant effect on women than men, due in part to hormonal differences and in part to different impacts on blood alcohol levels. A single drink typically causes higher blood alcohol levels in women than men due to differences in alcohol metabolism and body composition. Learn more about drinking, sex and gender from the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

It’s worth taking a closer look at the role of alcohol in breast cancer risk, which is the most common alcohol-related cancer in women. A recent meta-analysis (study of studies) found that drinking one standard drink per day was linked to a ten percent higher risk of postmenopausal breast cancer on average, with variable results across studies. About two more women out of 100 would develop breast cancer drinking one serving of alcohol per day, compared to less than one drink per week. These estimates are from a large Australian study with over 100,000 women, as described in the 2025 US Surgeon General’s report.

These risks can feel big or small, depending on how you look at them. For example, if our cancer risk changes from 10% to 13%, the relative change is large: 13% is 30% more than 10%! Yet, the absolute risk is fairly small: 3 extra cases among 100 people.

Another way to make sense of these numbers is by comparing them to other risks. A clever study estimated that the additional cancer risk from a weekly bottle of wine is similar to that of ten weekly cigarettes. To learn more about the cancer risks for various tumour types, check out this Fact Sheet from the US National Institutes of Health.

How reliable are these estimates of cancer risk?

How sure can you be that drinking 1 glass of wine a day increases your breast cancer risk from 11% to 13% in women? Or that a bottle of wine is similar to 10 cigarettes?

In short, not very. While we can say with confidence that alcohol increases the risk of certain cancers in a dose-dependent way, we should take the exact risk estimates with a grain of salt. Indeed, estimates of the impact of alcohol on cancer risk vary greatly from study to study (see this analysis of 572 studies and this analysis of 106 studies).

The challenge with defining the risks associated with alcohol stems from the type of evidence we use: observation studies. Observational studies are those in which scientists observe large populations to look for associations. In this case, they compare health outcomes in people who choose to drink different amounts of alcohol. These studies can give misleading results because people who drink different amounts of alcohol may differ in other ways that impact their cancer risk. For example, teetotalers may be more likely to exercise, eat fruits and veggies, and not smoke. These factors, called “confounding variables”, can make an association seem stronger (or weaker) than it actually is. Researchers attempt to “control for” these differences through study designs and statistics, but it’s virtually impossible to rule them out completely. To learn more, check out my post on confounding variables (confounders) for

.To precisely measure the effect of alcohol on cancer risk, we need the gold-standard scientific study - a randomized controlled study in which people are assigned to a certain group (placebo, drug, exercise, alcohol intake…) then followed over time. This type of study isn’t happening anytime soon for alcohol, smoking, or other any other known hazards.

To complicate things further, the data presented above are average risk estimates from mixed populations. The impact of alcohol on each of us depends not only on dose, tumour type, and biological sex, but also on exposure to other hazards (e.g. smoking), protective factors (e.g. eating fruits and veggies) and genetic susceptibility. It’s impossible to know how your health will be affected by a given amount of alcohol.

Closing thoughts

While it’s important to raise awareness about the potential harms of alcohol, I don’t believe we need to panic about every drink. As always, the dose makes the poison!

Personally, I feel comfortable having a few glasses of wine a week, knowing the risks are minimal at this level. Still, I decided to break my habit this year and tried “Dry January”. It’s now Valentine’s day and I’m still going strong. I’m not missing it as much as I expected and have been enjoying a some seriously delicious mocktails. I find that it’s still a great pleasure to treat myself to a tasty beverage, ideally with good company - even without the buzz.

You may feel comfortable with more or less risk than me, and that's fine. I just want to help you make an informed choice. If you don’t feel in control of your alcohol intake, please get support. One resource to start with is Rethinking Drinking from the National Institutes of Health.

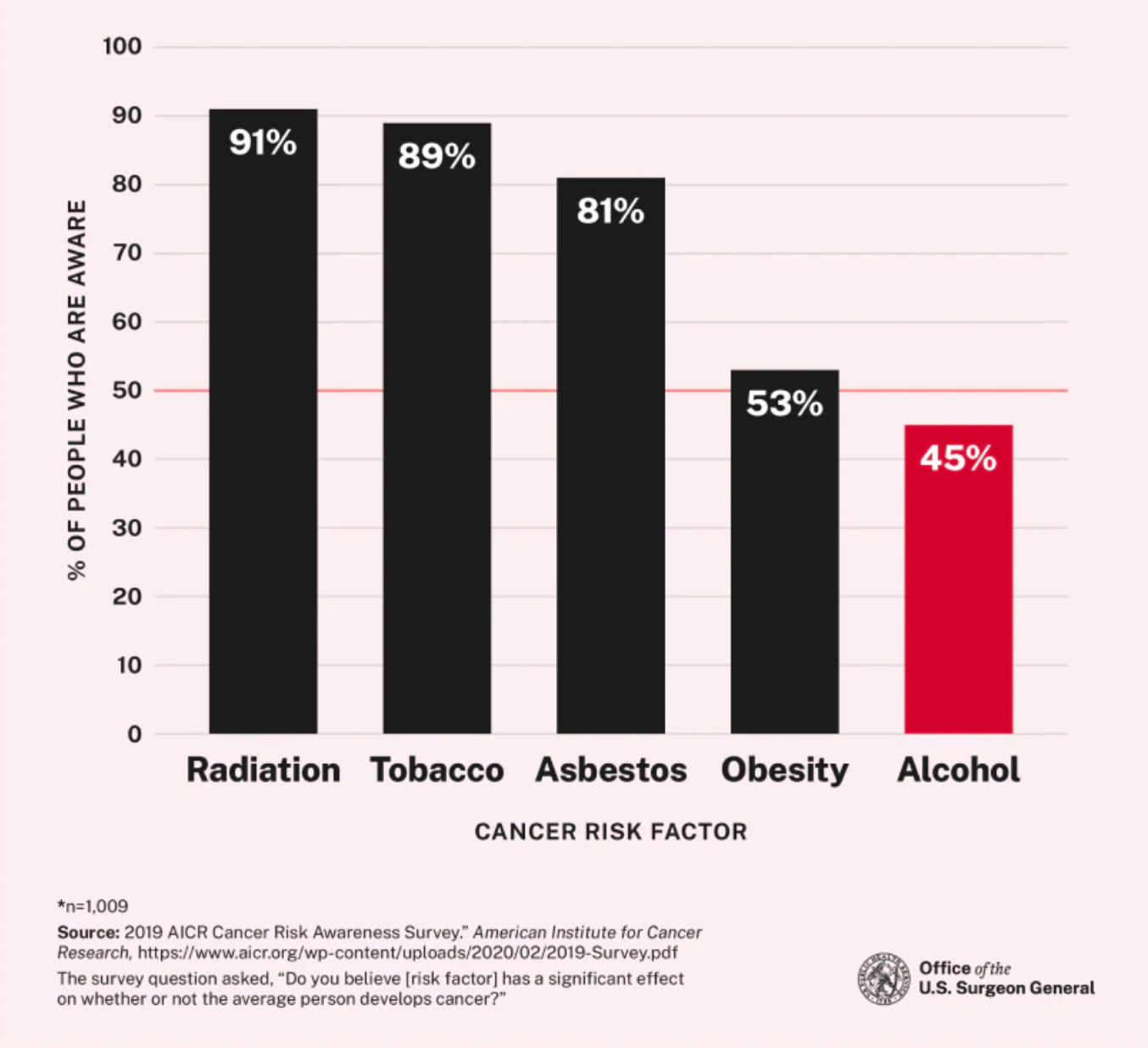

Last but not least, I encourage you to learn about other important yet unappreciated cancer risk factors, like obesity, lack of exercise, and low fiber diets (topics for another day!).

Yours in science and in heart,

Chana

P.S. We can dig into the impact of alcohol on other health outcomes another time (spoiler alert: it’s complex!)

Nerd Note: When discussing health harms, we must distinguish between a hazard and a risk. A hazard is something that can potentially cause harm (e.g. UV radiation, arsenic, tobacco, alcohol). A risk puts a hazard in context - a hazard poses a risk when we are exposed to a harmful dose. For example, UV radiation is a hazard, but 5 minutes of sunlight in Norway’s winter does not increase the risk of skin cancer, unlike spending summers in Mexico without sunblock. The WHO’s role is to classify hazards (carcinogens), and it puts alcohol into group 1a, alongside tobacco, UV radiation, and arsenic. The risk posed by alcohol to your health depends on dose and on personal factors that may impact cancer susceptibility.

References

Alcohol and Cancer Fact Sheet (National Institutes of Health)

Alcohol and Cancer Fact Sheet (World Health Organization)

Alcohol Use and Cancer (American Cancer Society)

Global interactive map of cancers attributable to alcohol (World Health Organization)

Chana...thank you for displaying this in a way that is easy to understand and allow the reader to come to their own perspective. I am heavily exploring what could be feeding my cancer through the diet that I choose to follow and how I can look to give my body the best possible chance in giving it a good old run for its money. Looking forward to exploring more of your content on this subject!

Very well written, concise, and informative. I appreciate the way you put stats into context (e.g. relative vs absolute risk). Subscribed!